The nonprofit Accelerator for America invests in economic and sustainable development projects across the U.S., including a planned expansion of this rail line in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Accelerator is part of the Justice Climate Fund, which is seeking EPA investment to advance its work. (Image credit: Accelerator for America)

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is set to distribute up to $27 billion to states, localities, nonprofits and community lenders next month. Made available through the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, the grants aim to support efforts that combat climate change and reduce air pollution, with a focus on low-income and historically disadvantaged communities.

Climate and environmental justice advocates have praised the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund for its stated intentions, but some are concerned about how equitably the capital will be deployed — and if it will really reach the locally-led organizations doing the hard work in communities most impacted by climate change and pollution.

What is the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, and why do we need it?

Air pollution is linked to an estimated 1 out of every 25 premature deaths in the U.S. — more than traffic accidents and shootings combined. Since most people don't want polluting sites in their neighborhoods, fossil fuel companies and other industrial developers historically sought out communities that didn't have the economic or political power to resist a new planned complex. These communities were most often low-income and had majority residents of color.

As a result, people of color and low-income people are more likely to be exposed to high levels of air pollution today, and as such are at greater risk of premature death. These communities also face outsized impacts from climate change, and their proximity to undesirable industrial sites can further slow economic development.

Established by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund aims to mobilize public and private capital to address these longstanding disparities. As does the Joe Biden administration's Justice40 Initiative, which looks to direct 40 percent of the overall benefits of certain federal investments — including those from agencies like the EPA — to communities that are underserved and overburdened by pollution.

What's coming from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund in March?

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund will distribute up to $27 billion across three separate grant competitions in March. These competitions are open to U.S. states, cities, towns, nonprofit organizations, and lenders like green banks and community development financial institutions (CDFIs), with the aim of ensuring communities actually benefit from the growth of sectors like clean energy in the form of well-paying jobs, economic development and reduced air pollution.

Applicants include the Justice Climate Fund, a coalition of nearly 20 organizations led mostly by people of color that support economic and sustainable development in underserved communities across all 50 U.S. states. Members include green banks, which use public funds and private capital to support clean energy and other environmental-related projects, and CDFIs, which make at least 60 percent of their investments in underserved low- and middle-income communities.

"We expect the EPA to make an announcement that will, I think, set this country in the right direction to address a long forgotten — and ignored — climate and environmental issue this nation faces," said Lenwood V. Long Sr., CEO of the African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs, which represents 76 Black-led financial institutions and is a founding member of the Justice Climate Fund. "I've been impressed with the administration's efforts to ensure communities of color are engaged in a direct way, at the community level, where they can really make a difference."

Marcene Mitchell, senior vice president of climate change at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and vice chair of the Green Bank of Montgomery County in Maryland, is similarly optimistic. "We expect that the March announcement will outline how the EPA intends to support a patchwork of newly energized green banks and other entities in a way that is impactful and lasting," she said. "These green banks and other nonprofits grew out of communities and have an important role to play in finding opportunities to provide communities with a strong and sustainable economic growth path."

Still, some questions remain about whether the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund will repeat the old patterns of investment that caused the country's environmental justice issues in the first place.

Will capital from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund really reach underserved communities?

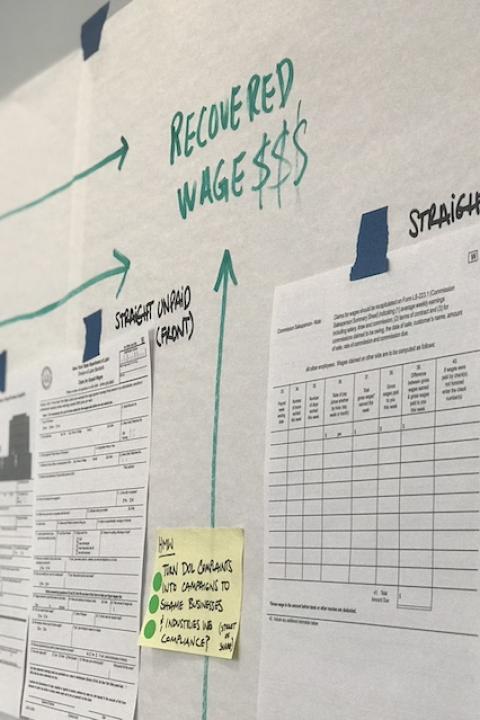

As the EPA looks to deliver significant capital to small organizations for the first time, growing pains are bound to happen. Last month, some small nonprofits that received grants from the EPA to address pollution in their communities told The Guardian they were ultimately forced to turn the money down as process requirements and paperwork became too much.

While concerning, the issue isn't as common as some feared when the story first broke. "I looked at the numbers: There were 132 awards made, but there were only five that declined the award because, in their mind, the requirements were excessive," Long said. "Let's face it, the EPA in the past has never focused upon community-based organizations on this scale and magnitude. The EPA is going to have to make some adjustments, but I was pleased to see that only five declined for various reasons. And I get it, if you're a certain size, it can be really difficult and grievous to meet some of those requirements."

Nonprofits aren't the only ones facing readiness issues as big EPA money comes to town. After decades of disinvestment, it will take education, consistent outreach, and trust to help residents of historically underserved communities understand how environmental programs can benefit them, Long said.

Imagine, for example, a nonprofit receives EPA funding to expand access to rooftop solar. Outreach coordinators go door-to-door to get neighbors involved, but what do those people — many who are struggling to meet basic expenses like rent, food and healthcare — really hear? To them, it likely seems that some out-of-touch person on their doorstep is trying to sell them a bill of goods, in the form of a significant upfront investment in solar panels that will take years to pay off. Tax credits and subsidies, plus funds made available from the nonprofit, could help reduce their upfront cost to zero and provide benefit right away, but residents are less likely to receive this message from unknown groups based outside their community that they do not know or trust.

"It's going to take a lot of education if we are going to be successful," Long said. "My fear is that those organizations who do not know anything about low-income and disadvantaged communities, who have not really worked in those communities, will be recipients of those funds and looking for organizations that they haven't worked with before to fill in the gap for their avoidance and for their neglect of the community. But they always show up when the money flows. That's my concern."

Community-led groups are ready and able to fill the gap

The good news is that EPA grant competitions, including the $6 billion Clean Communities Investment Accelerator, have a stated aim to invest in coalitions of nonprofits and community lenders — which individually represent decades of work in underserved communities and collectively touch all states in the nation with the ability to drive large-scale impact.

That includes groups like the Justice Climate Fund, founded by the Community Builders of Color Coalition to ensure EPA financing flows equitably to the communities it's intended to reach.

Along with the African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs, the Fund's membership includes Oweesta, which offers financial products and development services to CDFIs led by Native American communities. Borrowers associated with Oweesta have disbursed over $717 million in loans for small businesses, housing, agriculture and individual needs over the past two decades, with the goal of countering disinvestment in Native communities. The National Association for Latino Community Asset Builders (NALCAB), a network of more than 200 nonprofit organizations serving diverse Latino communities across the U.S. and Puerto Rico, is also a member, along with more than a dozen other groups led mostly by people of color.

"They've been doing more than Justice40 work with limited resources," Long said of these groups. "Now, they have a chance of governing and participating in the allocation of those funds — and ensuring that low-income, disadvantaged communities will not be neglected or be a recipient of trickle-down funds. And more importantly, they have the experience of knowing the community. They have trust in the community."

"A clarion call for community voices"

The bottom line is: The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund has major potential to address longstanding disparities that caused chronic disinvestment, poverty and pollution. "Many underserved communities and communities of color across the United States have had to assume an outsized and disproportionate amount of pollution caused by fossil fuels. We now have an opportunity to right that wrong," said Mitchell of WWF.

But it's up to concerned onlookers to remain vigilant and voice their support for community-led groups, Long said. "What has happened, and I hope the EPA recognizes this, is that those who have been working in Justice40 communities are not the big organizations that are well-funded, that have political strength, that have for years possessed the wealth of America," he told us.

"Isn't it interesting that when big money shows up, trickle-down economics is the pattern for America in moments like these? And if it happened now, in this year of 2024, an election year, what would that say about an administration that is looking for support?" Long continued. "This is a rallying cry for all who are serious about ensuring capital flow to organizations that have been working in the communities, living in those communities, have been doing work with less money but having results in those communities. It should be a rallying cry and it should be a clarion call for community voices."

Those interested in showing their support for community-led organizations vying for EPA funds can share their perspective with the agency on social media or amplify the voices of groups like the Justice Climate Fund and the African American Alliance of CDFI CEOs, he said.

"We need cheerleaders, we need ambassadors," he concluded. "We need those who are willing to sound the alarm for this moment. It's intended for our communities who have been left out."

Mary has reported on sustainability and social impact for over a decade and now serves as executive editor of TriplePundit. She is also the general manager of TriplePundit's Brand Studio, which has worked with dozens of organizations on sustainability storytelling, and VP of content for TriplePundit's parent company 3BL.